pediatric forum

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are relatively common infections during childhood that may affect any portion of the urinary tract, from the kidneys to the urethra. Pediatric UTIs are estimated to affect 2.4 to 3 percent of all U.S. children each year, and result in over 1.1 million office visits annually and an estimated inpatient cost of over $180 million.1,2

UTIs have a range of presentations, from uncomplicated cystitis to severe febrile infections, which have the potential to lead to renal scarring and chronic kidney disease. In the first year of life, boys are more likely than girls to develop a UTI. Uncircumcised boys in this age range have 10 times the risk of UTI than circumcised boys. After the first year of life, girls are much more likely to develop a UTI, with the overall childhood risk of UTI 2 percent for boys and 8 percent for girls.2

A recent study showed that up to one-third of providers may delay testing urine in patients that are high risk for UTI.3 Bladder infections do not typically result in long-term sequelae, but upper urinary tract infections may result in permanent renal scarring with inherent risk of subsequent development of hypertension or impaired renal function. Because of the possibilities of renal damage and scarring that may occur after febrile UTIs, providers should think of the possibility of a UTI in a febrile patient without an obvious source.

evaluation

While older children and adolescents can easily describe symptoms that point to a UTI as a likely diagnosis, one must have a high index of suspicion for UTI in children younger than 2 to 3 years of age as they cannot accurately describe their symptoms. When evaluating a child with a possible UTI, it is important to consider and note the following points in the history:4

- Patient age and gender

- First or recurring infection

- Febrile (>100.4°F) or nonfebrile UTIs

- Any known abnormalities of the genitourinary tract (identified on pre-or postnatal renal and bladder ultrasounds)

- Prior surgeries

- Family history of UTI

- Sexual history in adolescents

- Drinking and voiding habits

- Bowel habits (especially constipation and infrequent bowel movements)

- Associated nausea or vomiting

- Urinary urgency, frequency or dysuria

- Poor appetite or failure to thrive

- Lethargy

- Hematuria

Physical examination should include palpation of the abdomen, suprapubic region and costovertebral angles to determine if tenderness is present. Focused examination of the external genitalia should make note of any lesions, discharge, foreign bodies, tenderness, and labial adhesions in girls, or phimosis or meatal stenosis in boys.1

diagnosis

There is an association between delay in treatment of febrile UTIs and permanent renal scarring. In febrile children without an apparent source for their infection, clinicians should not delay testing for UTI.5 In these children, before administering any antibiotics, a urine specimen should be obtained and sent for both urinalysis and culture.4, 6, 7 A urinalysis is suggestive of a UTI when it shows positive leukocyte esterase or nitrite test results, or leukocytes or bacteria are seen on microscopy. These findings should be confirmed by urine culture.

In toilet-trained children, a voided urine specimen after properly cleaning the genitals should be sufficient to evaluate for a possible UTI.

A diagnosis of UTI is made in the presence of ≥100,000 cfu/mL of a single uropathogen. Contamination of the urine sample is suggested when there are fewer than 50,000 colonies or in the presence of multiple organisms.

In toddlers and infants not yet toilet trained, a specimen can be obtained in one of three ways:4, 6, 7

- Bagged urine specimen Bagged specimens are convenient, but in general they are only helpful if they are negative because they are often contaminated by perineal flora. When a urinalysis from a bagged specimen suggests a UTI, then a second urine specimen needs to be collected through catheterization or suprapubic aspiration to be sent for urine culture.

- Catheterization While this is more invasive, there is a significantly smaller risk of contamination of the specimen. Diagnosis of UTI requires both a urinalysis suggestive of infection and ≥50,000 cfu/mL of a single uropathogen.

- Suprapubic aspiration (SPA) This is the most invasive test, but also has the lowest risk of contamination. Diagnosis of UTI requires both a urinalysis suggestive of infection and ≥50,000 cfu/mL of a single uropathogen.

Asymptomatic bacteriuria is defined as 1) no pyuria and 2) the growth of a significant number of a single organism (traditionally >100,000 cfu/mL) in the urine sample of an asymptomatic child. This is commonly seen in children with neurogenic bladders, or those performing clean intermittent catheterization (CIC) and should not be treated with antibiotics.8

Just as asymptomatic bacteriuria should not be treated with antibiotics, one should also avoid treating symptoms in the absence of a positive urine culture. Symptoms such as urinary frequency, urgency, dysuria, abdominal, su-prapubic, or genital pain often accompany a UTI, but they are not specific for UTIs. When evaluating a child with these or other vague urinary symptoms, antibiotic administration is inappropriate in the absence of laboratory evidence of a UTI.

treatment

In general, oral and paren-teral antibiotic administration is equally efficacious for UTI. When administering empiric antibiotics, the choice of antibiotic should be based on local antimicrobial sensitivity/ resistance patterns (if available), and adjusted (if needed) according to the culture sensitivities.6, 7

Parenteral empiric antibiotics recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) for UTI include third-generation cephalosporins, gentamicin, tobramycin and piperacillin. Recommended oral agents include cephalosporins, sulfonamides and amoxicil-lin-clavulanate.6 Escherich-ia coli is the most common organism causing UTIs in pediatric patients, and any empiric antibiotics given should cover this bacterium. Antibiotic resistance is a growing concern, as E. coli isolates nationwide have shown growing resistance to trimethoprim-sul-famethoxazole (21.3-24 percent), ß-lactams (37.7 percent), and ampicillin (45 percent). There is a less than 1 percent resistance to nitrofurantoin.9, 10

For uncomplicated episodes of cystitis, it is recommended to treat with three to seven days of oral antibiotics. A post-treatment urine culture is not needed if the symptoms have resolved.

For episodes of pyelone-phritis, some patients may be treated on an outpatient basis, while others require inpatient antibiotic administration and close observation. Inpatient treatment is recommended for toxic appearing patients, those under 2 months of age, those unable to tolerate oral medications, or those in whom there is a concern for compliance. Once a patient is afebrile for 24 to 48 hours, a seven- to 14-day course of oral antibiotics is appropri-ate.4, 6, 7

bladder and bowel management

Any signs of bowel and bladder dysfunction (BBD) should be addressed, as these may contribute to increased risk of UTIs. Children should have regular, soft bowel movements. Treatment of constipation has been shown to decrease UTI recurrence.11 Primary care physicians can evaluate for BBD and initiate measures to address these problems.12

imaging

Imaging is not always required in children with UTIs, and is typically obtained in patients with febrile or recurrent UTIs. The AAP has issued evidence-based guidelines regarding the appropriate use of imaging.6,7 In order to avoid the expense and risks associated with invasive studies (those requiring catheterization or injection of radiotracer), they should be ordered appropriately and judiciously. There are three common imaging studies used in the evaluation of children with UTIs.

- Renal and Bladder Ultrasound (RBUS) RBUS is safe and appropriate to obtain while a UTI is being treated. It is important to obtain images of both kidneys and the bladder. Any febrile infant with a UTI should undergo an RBUS (especially those who have no documentation of a normal postnatal RBUS). Children 2 to 24 months should undergo RBUS as the only imaging study after a first febrile UTI. Children older than 2 years with recurrent UTI should undergo an RBUS.4, 6, 7

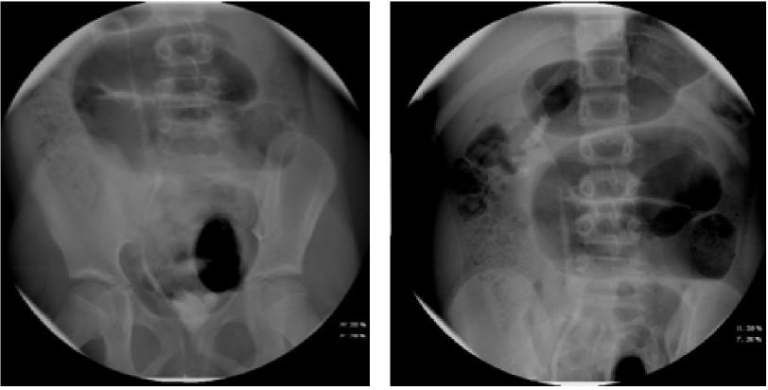

- Voiding Cystourethrogram (VCUG) (Figures 1 and 3) A VCUG is helpful in identifying bladder emptying, vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) or urethral obstruction. It should not be obtained until after a child is afebrile for at least 24 hours and is no longer symptomatic. It should be obtained in children less than 2 months with a febrile UTI, in the setting of abnormal anatomy on RBUS (hydronephrosis, renal scarring, etc.), or in other atypical or complex situations. It should be obtained in children 2 to 24 months following a second febrile UTI.6, 7

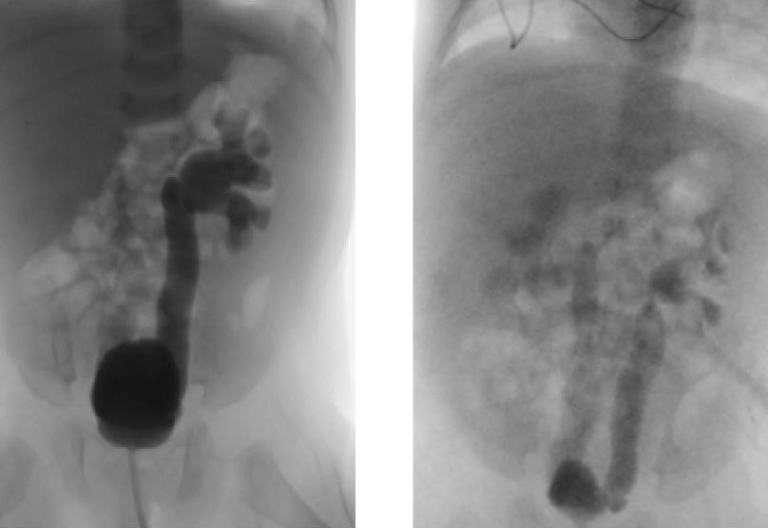

- Dimercaptosuccinic Acid (DMSA) Renal Scan (Figure 2) This is a nuclear medicine test, and should not be used routinely after a first febrile UTI, but may be helpful in identifying renal scarring later on. This test will show both renal scarring and active pyelonephritis, but cannot differentiate between the two entities. When evaluating for renal scarring, DMSA scan should not be obtained until four to six months from the time of acute pyelonephritis.8

antibiotic prophylaxis

Bowel and bladder dysfunction is a major risk factor for recurrent UTIs. The question of whether or not to place a child on prophylactic antibiotics has no universally applicable answer, and there is some controversy regarding the use of antibiotic prophylaxis in children with VUR. It is most commonly used in children with VUR, and more specifically is generally beneficial in children less than 1 year with VUR, or children over 1 year with high-grade VUR. When looking at all children, antibiotic prophylaxis has been shown to substantially reduce the risk of UTI recurrence in patients with VUR, but does not alter the development of renal scarring.13 A Swedish study has shown that in girls between 1 to 2 years of age with high-grade VUR, prophylaxis decreases both UTI recurrence and new renal scarring.14

surgical management of VUR

Multiple options are available for the surgical correction of VUR, including endoscopic, laparoscopic and open techniques. Resolution of VUR is expected in 98.1 percent for those undergoing open surgery and 83 percent for endo-scopic therapy. Surgical intervention is considered for higher grades of VUR, breakthrough febrile UTIs or recurrent infections while on antibiotic prophylaxis, or in children with evidence of renal scarring. Prospective randomized controlled trials have shown a decreased occurrence of febrile UTIs in patients after open surgical repair when compared to patients receiving antibiotic prophylaxis.15

when to refer

In some cases, referral to a pediatric urologist should be considered. These situations include patients with VUR (especially high-grade), abnormal RBUS results, congenital genitourinary tract anomalies, recurrent or severe UTIs, febrile UTI in an infant, or symptoms of urinary urgency, frequency or enuresis in the absence of UTI.

view the entire Winter 2018 pediatric forum

references

- Copp HL, Schmidt B. Work up of pediatric urinary tract infection. Urol Clin N Am. 2015;42:519-526.

- Freedman AL. Urologic diseases in North America project: Trends in resource utilization for urinary tract infections in children. J Urology. 2005;173:949-954.

- Bunting-Early TE, Shaikh N, Woo L, Cooper CS, Figueroa TE. The need for improved detection of urinary tract infections in young children. Front Pediatr. 2017;5:1-10.

- Stein R, Dogan HS, Hoebeke P, et al. Urinary tract infections in children: EAU/ESPU guidelines. Eur Urol. 2015;67:546-558.

- Shaikh N, Mattoo TK, Keren R, et al. Early antibiotic treatment for pediatric febrile urinary tract infection and renal scarring. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170:848-854.

- Urinary tract infection: Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and management of the initial UTI in febrile infants and children 2 to 24 months. Pediatrics. 2011;128:595-610.

- Reaffirmation of AAP clinical practice guideline: The diagnosis and management of the initial urinary tract infection in febrile infants and young children 2-24 months of age. Pediatrics. 2016;138:1-5.

- Saadeh SA, Mattoo TK. Managing urinary tract infections. Pediatr Nephrol. 2011;26:1967-1976.

- Edlin RS, Shapiro DJ, Hersh AL, Copp HL. Antibiotic resistance patterns of outpatient pediatric urinary tract infections. J Urology. 2013;190:222-227.

- Zhanel GG, Hisanaga TL, Laing NM, et al. Antibiotic resistance in Escherichia coli outpatient urinary isolates: Final results from the North American Urinary Tract Infection Collaborative Alliance (NAUTICA). Int J of Antimicrob Ag. 2006;27:468475.

- Loening-Baucke V. Urinary incontinence and urinary tract infection and their resolution with treatment of chronic constipation of childhood. Pediatrics. 1997;100:228-232.

- Shaikh N, Hoberman A, Keren R, et al. Recurrent urinary tract infections in children with bladder and bowel dysfunction. Pediatrics. 2016;137:1-7.

- Hoberman A, Greenfield SP, Mattoo TK, et al. Antimicrobial prophylaxis for children with vesicouret-eral reflux. New Eng J Med. 2014;370:2367-2376.

- Brandström P, Jodal U, Sillén U, Hansson S.The Swedish reflux trial: Review of a randomized, controlled trial in children with dilating vesicoureteral reflux. J Pediatr Urol. 2011;7:594-600.

- Peters CA, Skoog SJ, Arant BS Jr, et al. Summary of the AUA guideline on management of primary vesicoureteral reflux in children. J Urol. 2010;194:1134-1144.

care that goes above and beyond

Because every child deserves care that goes above and beyond, Dayton Children’s provides compassionate, expert care for kids of all ages. Find a provider, schedule an appointment, or learn more about conditions we treat today.